Outsourcing Outfits: Why Your Clothes Stopped Being Made in America

written by Thomas Starr

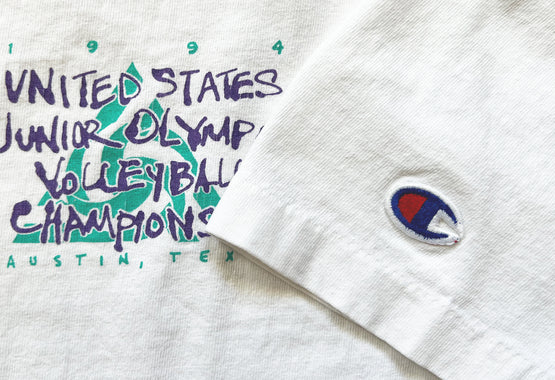

If you’ve ever checked the tags of your vintage clothing, you’ve probably noticed that most of them were made in the United States. However, tags on clothing made today are much less likely to bear this label, with Asia and Latin America now dominating the global textile industry. How did this shift happen? What made American clothing companies decide to offshore production and when did this happen? To answer these questions, let’s take a dive into the dark history of the American textile industry and explore the factors that led to your clothing no longer being made in the USA.

The Origins of the American Textile Industry

In the mid-20th century, the United States was a hub for textile and apparel manufacturing. American households spent a significant portion of their income on clothing, and nearly all garments were made domestically. This was the result of a centuries-long process of industrialization, beginning at the same time as the founding of this country. In the colonial period, fine imported textiles were costly items, and clothing manufacture—from raising raw materials to sewing—was largely a household industry in the United States. However, as industrialization took hold, the landscape changed significantly. In the late 1700s, the textile industry began to take off in England, and many Americans wished to see the same development in the United States. However, English law made it illegal to carry loom designs out of England. Samuel Slater evaded this law by migrating to the United States and bringing with him the knowledge of power looms in 1789. His expertise helped Moses Brown build the first water-powered spinning textile mill in America. After Eli Whitney invented the cotton gin in 1793, the cotton textile industry grew rapidly in the U.S. Within several years, Francis Cabot Lowell established the first textile factory in the country, known as the Boston Manufacturing Company. Lowell’s mill integrated all tasks, converting raw cotton into cloth, and employed single girls who became known as the Lowell Girls. Many people see the establishment of the Lowell mill as the start of the Industrial Revolution in America.

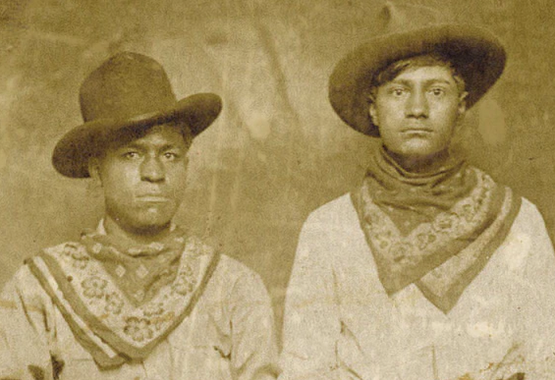

“King Cotton” and Slavery in the 19th Century

By the mid-1800s, the U.S. textile industry was thriving. Cotton became known as “King Cotton” in the South, the Southern United States became the chief cotton supplier, and The Boston Manufacturing Company was responsible for a significant portion of cotton production. However, this massive industrial growth was not merely due to chance. Instead, the American textile industry was built upon the backs of enslaved African-Americans who were forced to farm cotton, as well as indigo used for dying fabrics, in the South. Eli Whitney’s invention of the cotton gin at the end of the 18th century led to the explosion of the cotton industry in the south. As such, the demand for slaves to grow and harvest this cotton also skyrocketed, leading to nearly 4 million slaves in the South by 1860. Thankfully, this system ended in 1865 with the Union’s victory in the American Civil War, but the exploitative nature of the cotton industry survived through the institutions of sharecropping and Jim Crow in the south. These policies restricted the economic and physical mobility of former slaves, giving them few other options but to remain on the farms on which they were enslaved and continue to grow and harvest cotton for miniscule wages. This would continue until the middle of the 20th-century, when further industrialization decreased the need for manual labor in the cotton industry. It was also at this time that the American textile industry reached its peak, all due to over a century of incredibly exploitative labor practices.

The Peak of American Textile Manufacturing

In the first half of the 1900s, American textile manufacturing reached its zenith. Factories hummed with activity, producing fabrics, garments, and other textile goods. The industry was a major employer, providing jobs for thousands of workers across the country. While labor conditions in the cotton industry were terrible, conditions in the textile industry were drastically improving thanks to unionization. Two influential unions emerged during this period: the International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU) and the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America.

The International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU)

The ILGWU, founded in 1900, played a crucial role in shaping the textile industry. It primarily represented female garment workers, many of whom were immigrants. The ILGWU fought for shorter workdays, safer factories, and collective bargaining rights. Their efforts led to significant improvements in working conditions, but the struggle was ongoing. The infamous Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in 1911, where 146 workers died due to unsafe conditions, galvanized public support for labor reforms and strengthened the ILGWU’s cause. The union would continue to advocate for American garment workers until its dissolution in 1995.

The Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America

The Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America (ACWA) formed in 1914, focusing on male garment workers. Like the ILGWU, the ACWA advocated for better wages, job security, and the right to organize. They successfully negotiated collective bargaining agreements with manufacturers, ensuring fair treatment for their members. The ACWA’s influence extended beyond the workplace; they actively participated in political and social movements, championing workers’ rights and social justice. The ACWA would also dissolve in 1976, in large part due to the shift to overseas production of clothing.

The Shift to Overseas Production

Despite the gains made by American textile unions, the industry faced challenges. As the 20th century progressed, manufacturers sought cost savings and efficiency. As a result, the shift toward overseas production gained momentum. Lower labor costs in developing countries and the efficiencies of global supply chains encouraged manufacturers to move their production overseas and trade policies limiting import restrictions and duties allowed for this move to happen. Due to lower labor costs, manufacturers were able to produce much larger quantities of clothing at much lower costs, thereby decreasing the cost of clothing for American consumers. As a result of this, Americans now only spend approximately 3.8% of their income on clothing, a massive decrease from 9% in 1950. While this may seem beneficial, these gains for consumers come at a drastic cost. Despite America remaining the largest apparel market, very little clothing continues to carry the “Made in USA” label. Additionally, between 1990 and 2011, approximately 750,000 apparel manufacturing jobs disappeared in the U.S. These jobs were transferred to developing countries, where labor conditions are much worse. Almost everyone is familiar with the concept of a “sweatshop,” a very real phenomenon that sprung up as a result of the shift towards overseas clothing production. While the globalized textile industry does provide jobs in developing countries, the conditions faced in these jobs are far below ethical standards.

Conclusion

The shift towards overseas production is responsible for the massive decline of the American textile industry, despite its dominance in the early 20th century. This shift has also resulted in poor labor conditions being experienced in foreign garment factories, as Western clothing companies seek to maximize profits by minimizing labor costs. However, this unethical treatment of workers is far from a first for the industry, as it can trace its origins back to “King Cotton” and the institution of slavery in the Southern US. As consumers, we have a responsibility to change this unethical practice by making more informed clothing purchases. The most ethical way to buy clothing is of course to buy second-hand, though consumers still ought to research the new clothing they buy to assure that it isn’t made using sweatshops or child labor. Together, we can vote with our wallets and build a more ethical clothing industry.