Thrift Stores Are Everywhere, But Where Did They Come From?

by Corvus Snarr

Thrifting today is nothing like it used to be. Right now, it means hopping from store to store, sifting through aisles of slightly used-to-mostly abused goods. It means digging through the Goodwill Bins to provide an income, looking for things to repair, restore and resell. It means making a tiny dent in the over 14 million tons of textile waste thrown away by Americans each year.

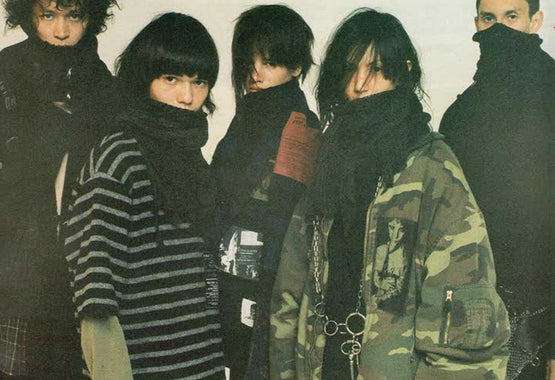

Technology has brought thrifters together, too. Many are posting videos of heavy thrift hauls or their POV vlogs shopping at local flea markets online — squealing excitedly at whatever cool piece they end up taking home. It’s a growing trend unmatched by anything in retail right now.

There’s a lot of potential that comes with thrifting, and an imaginative mind can run wild with ideas. However, it wasn’t always the cultural monolith we see today. According to the book, “From Goodwill to Grunge: a History of Secondhand Styles and Alternative Economies” by Jennifer Le Zotte, it took this country a long time to realize the awesome power of secondhand shops.

The people of the past didn’t have the same definition of thriftiness we do today. Being “thrifty” to a person in the late 1800s was all about saving money, learning how to darn socks and stretching the flour and lard in the pantry as far as it could go. No one thought about donating an old dress to charity. Old clothes were deconstructed and put to use making an apron, or a shirt, and then once worn through, cut into washrags or stuffed into furniture.

People didn’t throw things away, or hand out gently used items to strangers on the street, adds Le Zotte. Even the rich upper class used everything they had until that item was spent. Imagine that, a Kardashian wearing the same style for several consecutive seasons. Things have certainly changed.

There were places to buy secondhand items, though. In America, these shops were predominantly run by Jewish immigrants hoping to scrape by. However, rampant antisemetism made it difficult for them to make a living on their own. Mainstream society saw to it that buying from these shops (and from the people who ran them) was unacceptable. They were rumored to be dirty and for the lower class. Fictional stories have been found written in local papers as early as the 1840s where the main characters met their untimely end by contracting a disease — such as smallpox — from a thrifted garment. Needless to say, it was not popular to pop tags.

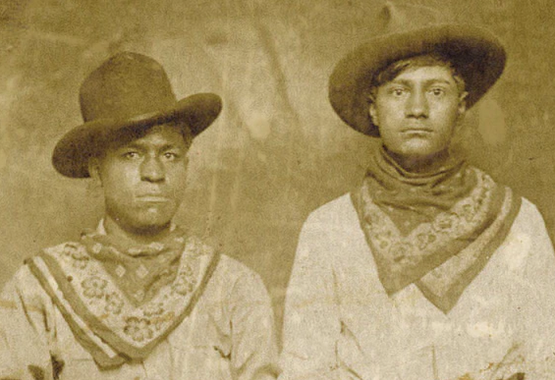

[Salvation Army California, ca. 1890s]

It was in 1897 when a major shift happened in the secondhand industry, in the form of the newly founded Salvation Army in the U.S. (it had been a fixture in the East End of London since 1865). Goodwill Industries followed suit quickly after in 1902. Both are still major players in the game today.

The Salvation Army saw opportunity in secondhand items and began sending volunteers door to door, collecting gently used goods to give to the less fortunate. At the start, these volunteers wore ragged clothes and broken shoes. They did so to signify that they had turned away from the frivolity of the average, upper-middle class American, even though many of them were of an upper-middle class status themselves. Dressing “like the poor” was thought to build trust. They wore the clothing they gathered as a way to signal to others they were more pious and helpful to the destitute communities they in fact were servicing.

Eventually, the Salvation Army leaned a lot more into the military's influence, coming up with uniforms and even following the standard rankings of the U.S. Army in its own office. The leader at the time in 1904, Evangeline Booth, spearheaded the PR issues brought on by antisemitism and concerns of unhygienic practices. She toured around the nation with a group of women called “slum sisters” — costumed in essentially sackcloth and ashes. These sisters would take the stage and praise the efforts of the Salvation Army, slowly convincing the public that it was hygienic and socially acceptable to buy thrifted goods. Evangeline even wrote a musical titled, “The Commander in Rags.”

She wasn’t the only one doing so, however. At the same time, Goodwill Industries was boasting of its large and diverse workforce. While both companies lauded their cleanliness and tried to pattern their image after big box department stores that were popular, Goodwill focused on its ability to give people a second chance. It regularly hired the disabled, marginalized and downtrodden.

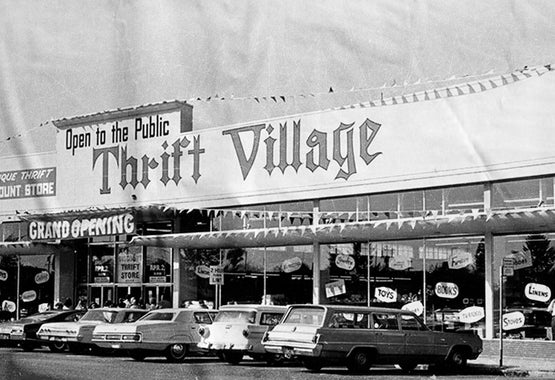

[Early Goodwill in Minnesota, 1919]

These were the people lifting themselves up by the bootstraps, the company highlighted. The beginning of the American Dream. Employees of the early Goodwill stores were the good, hard working poor people of America, and they were to be admired for their tenacity (unless, of course, they were Jewish). Remember how it all started with immigrants trying to make a living? Well, you see, both Goodwill and the Salvation Army are Christian organizations. And unfortunately, it was the Christianization of thrifting that helped make it palatable to the rest of the country.

Of course, that wasn’t the only thing that brought thrifting to the forefront. As the industrial revolution started booming, so did the thrifting industry. Suddenly, it was easier to buy new clothes, get new appliances and find home decor. It was a time of so many choices for the American consumer, all of them shiny and new. Suddenly, people had too much stuff. There wasn’t enough room, and so donating became synonymous with spring cleaning.

It was vital thrift shops kept up with the demand for diverse products. Luckily, the factories where many of these products were manufactured needed workers, which led to the rapid boom of urban areas. People were moving their families into smaller apartments in cities, closer to where they worked. They donated to the stores nearby, creating an increase in supply. Once the donations were sorted and priced, there were so many options for people to choose from. By the time of the Great Depression, these shops did their best to mimic the variability and organization of department stores to keep their status of acceptable, affordable alternatives.

Like with all things of today, thrifting is closely tied to consumerism and the social dynamics it represents. Changes throughout U.S. culture in terms of comfort, affordability and demand not only increased possessions in the home, but also the trash thrown out of them. Today’s thrifting, vastly different and more inclusive than before, shows the need for people to accept the past for what it was, and move forward with what can be.