The Evolution of the Smiley Face Graphic Through Time

You know it. He knows it. They all know it. It's the brightly grinning yellow Smiley Face, an iconic image that's uplifted billions through decades worldwide. But like with other cultural mainstays, sometimes these things simply ... exist. Many have likely written it off as just something that came to be, no real drama right? But as one digs deeply into the history of the Smiley, what's found is a dramatic history, one that spans generations alongside some of the most important underground movements humans have ever developed.

For over 60 years the Smiley has done what no other doodle has: it's lived.

1960s

Even though one of the first human-drawn smiley faces appears on a 4,000-year-old water jug, the actual history of the pop cultural Smiley begins in the late 1950s to the early 1960s. This is when it starts to land on things like movie posters, advertisements and on New York's WMCA “Good Guys” promotional sweatshirts (famously worn by a young Mick Jagger).

The man credited as the original creator, however, is commercial artist Harvey Ball. In 1963, the State Mutual Life Assurance Company in Worcester, Massachusetts, merged with another company, which sent office morale down the drain. To try and lift everyone’s spirits, the company hired Ball to create a happy graphic they could put on things like pins and cards to hand out to employees.

It took Ball all of ten minutes to doodle out the first known Smiley, and was paid handsomely for it at a measly $45 (about $406 by today’s standards).

“I made a circle with a smile for a mouth on yellow paper because it was sunshiny and bright,” Ball was once quoted. “You can take a compass and draw a perfect circle and make two perfect eyes as neat as can be, or you can do it freehand, and have some fun with it. Like I did. To give it character.”

The original face was initially printed on 100 pins. They became so popular around Mutual’s office that another 10,000 were produced shortly thereafter. This is when Ball should have acted on a trademark, because it eventually found its way onto posters, signs, cards and other office materials. His design appeared to have worked. And it was popular. But he never pulled the trigger on making the design officially his.

-----

1970s

What Ball didn’t do with his Smiley, others did. In 1970, having randomly seen the design and needing a new marketing scheme for their Hallmark shops, brothers Bernard and Murray Spain took the idea and profited. After tweaking the design a little to be a bit more standard and symmetrical — and adding the phrase “Have a Happy Day” — the two brothers began putting the graphic on pretty much everything. (This was actually a quite common industry practice back then, to take others’ commercial work and reuse it.)

Within the first few years of doing so, the brothers raked in over $1.2 million in sales — equal to about $10 million today.

As Jon Savage of The Guardian once put it: “The fad hit the post-1960s mood: a traumatized American public turning to visual soma in order to forget the war in Vietnam and presidential meltdown.” (Sounds awfully familiar, don’tit?)

For what it’s worth, the Barnard brothers never claimed to having invented the smile, just the monetization of it.

Yet even though the two made millions off of someone else’s idea, the brothers actually never saw where business trends were going either. Because months later someone else finally did smarten up and trademarked the image: a young journalist by the name of Franklin Loufrani.

In 1971, Loufrani secured a French trademark of the Smiley and began licensing out the graphic to other companies. The design would go from 0-100 in a matter of years because of his upbeat tenacity. The man knew how to market and initially had it printed onto 10 million stickers and handed them out for free to anyone who would take them. The image began appearing on bumpers, railings, walls, toilets — basically everywhere anyone happened to look. Big brands took notice, first Mars candy, then Levi’s … then the world.

-----

1980s

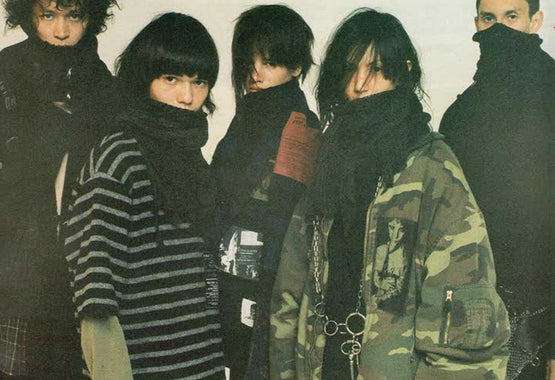

This is the decade the Smiley would be tested on all fronts. Seeing how well it did with France’s own hippie-type revolution of the ‘70s, Loufrani kept pushing the image into youth culture as it came. Along with the dramatic growth of the synthesizer market, popularity of new wave artists and the birth of a brand new type of electronic culture called “rave,” he brilliantly found ways to keep the image churning in cash, often reaching out to DJs to use it for album covers and t-shirts.

“He didn’t fight the adoption of the logo into something else,” says Nicolas Loufrani, Franklin’s son and now part owner of the franchise. “My father didn’t care. He’s never cared about how people think. He is an unconventional person who always wants to try new things.”

And what a new thing electronic music was. While small pockets of it were beginning to forge new identities around the world like in Chicago’s nightlife district, London’s historical Shoom acid-house night is said to have used the Smiley on its fliers first, latching onto the psychedelic nostalgia of it from decades past.

“The smiley symbol totally reflected the feeling and ethos of Shoom,” says founder Danny Rampling. “The positivity, love, unity, fun and happiness.”

Shoom’s graphics designer, George Georgiou, once said about it: “Danny insisted I use the Smiley-face symbol, which I wasn’t that keen on. So I made the Smileys tumble down the page either side of the text. Of course they looked like pills, which people picked up on.”

Authorities eventually picked up on it too. Worldwide, the struggle to keep Ecstasy off the streets raged in most every developed country. Headlines battling long drug-fueled club nights appeared alongside raving’s unofficial Smiley mascot giving it an undeserved reputation.

Said Loufrani’s son: “They were using smiley faces to show how bad rave culture was. They’d hold up a smiley and say, ‘This is criminal!’”

-----

1990s

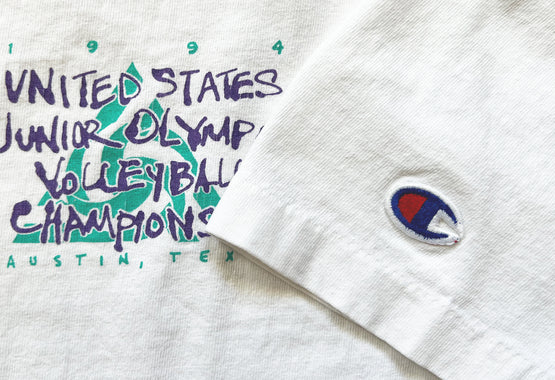

Stateside, another mainstream cultural movement was taking hold against the underground vibe of the raves. Grunge was pushing through the suburbs of America like a hot knife in butter. Popularized by late-night MTV appearances and anti-sports movements like skateboarding, Grunge would also adopt its own versions of the Smiley, most notably when Nirvana’s second album was dropped and a reworked, drunken version of it was featured on the release show’s flier. That same year it appeared on t-shirts and other memorabilia too, placing it in lockstep with what would become one of the most popular rock acts in history.

Different versions of it permeated youth culture in America throughout the entire decade too. Some were original reworks like WWE wrestler Mick "Mankind" Foley and his leather-bound logo or Smiley the Psychotic Button, a recurring comic book character in the Evil Ernie series.

-----

2000s

Ever the ones to be keen to upcoming trends, the newly named Smiley Company began to experiment with small digital faces that ran the gamut of human emotion. In 1999, the company rolled out 470 of them which would later come to be known as the first-ever set of emoticons. The Loufranis licensed them to mobile behemoths of the time, Nokia and Samsung, to be used with their cell phone operating systems.

The company’s slogan became: “The birth of a new universal language.”

Eventually, Apple and Microsoft would create their own sets of original emoticons. As technology became more advanced, the little characters slowly immersed themselves inside a whole new form of communication, texting.

“When emojis started to pick up, we were seen as the originator, and it gave us a renewed credibility,” says Nicolas. “The smiley was cool again.”

-----

Today

Of course, nothing that permeates American culture so deeply isn’t without its monetary drama. Currently, a legal battle over who owns the Nirvana smiley is still ongoing in court. The story is a winding dialogue of semantics between fashion designer Marc Jacobs and Kurt Cobain’s estate (and now someone else has stepped into the fold who has a different story on its origins entirely).

As for Franklin and Nicolas Loufrani, the father and son duo still pull in over $500 million a year licensing out the iconic graphic. It works with over 300 licensees including McDonald’s, Coca-Cola, Volkswagen and Lee.

Its original creator, Harvey Ball, passed away in 2001. He never made a dime on the design after he was initially paid for it in 1963.

“He was not a money-driven guy,” Ball’s son told the Worcester Telegram & Gazette shortly after he passed. “He used to say, ‘Hey, I can only eat one steak at a time.’”